After living and working in the US and Europe, the goal for living in Japan was to just dive deep into something different and push further outside of my comfort zone – trying to make the uncomfortable things become comfortable which is a theme to how I like to live my life.

There’s so much that first meets the eye that is hard to not like about Japan: Immaculately clean, very organized, incredibly nice and polite people, highly functional, and great food. This was easy to pick up the first time I visited Japan, but now actually living, commuting, and immersing for a longer period, things about Japan begin to surface that are not immediately recognizable to an outside (or briefly inside) observer.

As I connected with esteemed Japanese Darden alum before settling into the country, I was surprised that nearly each one asked, “But why Alex-san do you want to come to Japan, we’ve had no growth for years.” I knew about some of Japan’s more recent economic struggles, but it seemed like an odd question. After a month I’m beginning to better understand why. Here are a few of the things I’ve found surprising during my first month:

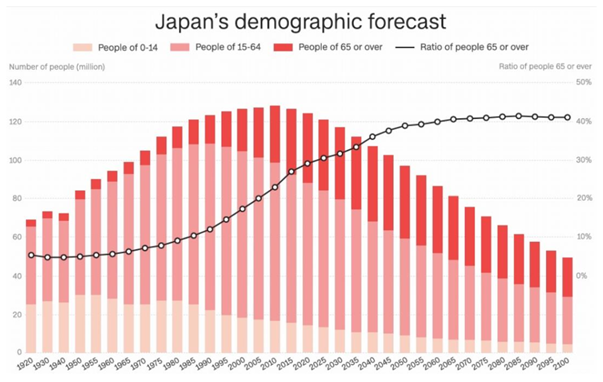

Significance of the population decline

A key headwind for the future of Japan is its aging population. Sure, some countries are facing similar issues and a country like Germany has had a stagnant population for decades, but the current estimates anticipate the current population of ~125m to shrink to less that 100m by 2050 (which isn’t that far away). 20% of the population just gone.

Language barriers

I didn’t think much of this at first. I’m in Japan so people speak Japanese. Why would I expect them to always speak to me in English? I’m no longer in the US. It wasn’t until I heard a lecture (from a Japanese businessman) on barriers Japanese firms are facing when expanding abroad and that the main inhibitor was lack of English proficiency. Business is global. The global business language is English. If you don’t know English, it’s hard to do business globally. Simple, but until I heard this topic debated, I wouldn’t have told you it was a problem in Japan.

Gender inequality

Japan is 116th on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report. 116th. Well below China and not very far from Afghanistan which is mind blowing for a G7 nation. Daily observations made this clearer such as women only subway cars, women-only lifting and stretching areas at the gym, rarely seeing women in leadership positions in the government or private business, and the Minister of Women Empowerment is a man. Yes, the national voice of women in Japan is a man’s.

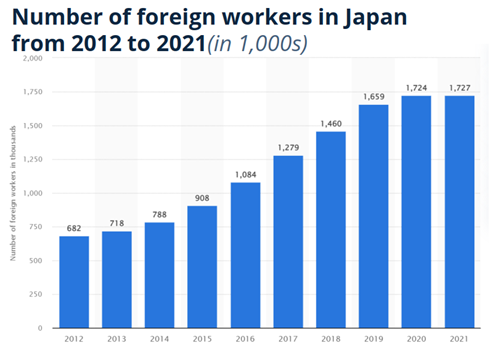

How still very insular the country is

Historically, Japan insularity has been well documented, but it’s still very easy to see hesitancy toward outsiders. Japan currently has one of the lowest rates of immigration in the world at just 2% of the population. As of October 2022, I was surprised to see that Japan was still very much locked down from COVID, allowing only 50k daily tourists for guided tours only meaning you can’t just come to Japan without being a part of a structured tour group. They finally released all restrictions later that month, close to three years after the start of COVID and really only second to China in their inflexibility with living with the virus. Another telling factor of its insularity is how few Japanese hold a passport. Japan is widely recognized as having the strongest passport but only 20% of the population actually has one. How ironic is it to have the strongest passport that nobody uses?

Even one of their most attractive qualities that everyone loves, Japanese food and agriculture products, has been a struggle to export until recently when the government created a separate ministry to enhance the export and tech capabilities in the food value chain to finally start exporting their expertise to the world. Japan is 8th in agricultural production by volume but 43rd in agricultural exports which is the widest place margin by far amongst the top producing countries.

Resistance to change

Japan has such a rich storied culture and one centered around respect for the hierarchy and a fondness for doing things the way they’ve always been done. I heard a lecture from Yoshihide Suga, Japan’s former Prime Minister who was also part of the late Shinzo Abe’s cabinet and spearheaded many of the regime’s initiatives during these terms. If I could summarize the theme of his lecture, it would be “breaking down silos.” Suga-san mentioned the many “silos” within the government and how difficult it can be to move quickly. From the slow movement of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, to opening of more channels to export Japan’s great agriculture products, to getting fertility treatments covered by the National Healthcare systems, Suga-san had to physically create brand new channels which avoided the old bureaucracy to get things done.

I spoke to other Japanese executives with similar themes of rigidity coming to light. One argued that the Japanese are actually not resistant to change, mentioning that they change when there are certain ‘earthquakes’ and he specifically referred to natural disasters, major crisis, etc. Seems to me that the Japanese change when there is literally no other option.

The “inverted V” relationship, with A at the apex and B and C at the two lower ends, is an analogy for how rigid the society (especially in your professional career) can be. Yes, this signifies the general hierarchical structure but also the fact that, for example, G, cannot have a relationship with A without first going through B or C. As the kids say, “there’s levels to it” and Japan is stuck in them to a fault.

Don’t get me wrong, Japan is a lovely place and will now forever have a special place in my memories. It is so unbelievable pleasant to live here. There’s virtually zero crime. I could leave my belongings in a public space and come back hours later to them undisturbed. No one has a gun. The last gun violence was from a home-made firearm. In America, guns are stocking stuffers. People are civil. No Karen’s complaining about a mask mandate, no sharp elbows in public, no phones blaring on speaker. Everything is immaculately clean. I’d rather lick the Tokyo subway poles than even touch anything in the New York City Subway. I’ve been struck several times by fabulously fresh bakery smells wafting through the Tokyo subway system. Ever get a waft of what’s cooking in the New York City subway? But Japan’s survival depends on change. Will this change also come at the expense of those core things we love about Japan?