We’re having a classic run on the banks – not necessarily something I thought I would never see happen, but it’s still equally surprising especially considering I was still an undergrad during the GFC so I wasn’t paying as close attention when it was unfolding.

Just like any other bank, Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”) takes deposits which substantially all come from startup companies. Those deposits are liabilities owed to the depositors (startups) whenever they demand their money. However, the deposits are not stuck under the mattress at SVB, but rather are invested in order to make returns while they wait for the funds to be requested by the depositors. To ensure the timely return of deposits, banks engage in maturity transformation which attempts to “match” the maturity of their investments to their best estimate of when they will need to return the deposits. For example, if depositor A is likely to demand their funds within the next year, it wouldn’t be wise for the bank to invest in a security with a 5-year maturity. However, if depositor B is expected to park his/her money at the bank for 10 years, a longer-term maturity investment yielding higher returns may be appropriate. Sure, this matching doesn’t occur on an individual basis, rather the banks will estimate the percentage of depositors who are likely to demand their funds in the short term vs. those who are likely to have a longer deposit period and invest accordingly.

SVB had a high concentration of their investments in long dated fixed income securities, both vanilla bonds and Mortgage-Backed Securities (“MBS”). Typically, a fine portfolio of assets (as long as the MBS’s aren’t 2008 MBS’s…), but not so fine in a rising interest rate environment like we have today. When interest rates rise, the value of bonds and other fixed income securities fall because the market is now paying more yield than the yield of those original bonds. Here is the accounting magic though: Because these securities were classified as “held-to-maturity”, the accounting rules say you don’t “mark to market.” Said another way, SVB didn’t have to reflect the true value of these underwater bonds on their balance sheet. The accounting standards would say that since SVB’s plan was to hold them to maturity, they will realize the full value of the bonds at that time – only if SVB sells those bonds before maturity would the loses crystalize. And this is exactly what they did.

After the sale of these underwater bonds, a hole on their balance sheet was created which caused them to i) sell additional shares to the market and ii) take a cash infusion from a private equity fund. Anytime companies need to go to the market and raise new equity without warning, it’s going to be a panic and panic is what happened. Because there is now concern as to the liquidity of SVB, startups began withdrawing their deposits which was exacerbated by the advice of their venture capitalists, especially big names like Peter Thiel. The tricky thing with banking startups is that they’re only typically holding 12-18 months liquidity before they raise their next fund – this means that they can’t afford SVB to freeze withdrawals for even a short time, so the panic was quick and sharp. Maybe a bit different if you have mature companies with i) consistent cash flow generation and ii) cash spread across many banks.

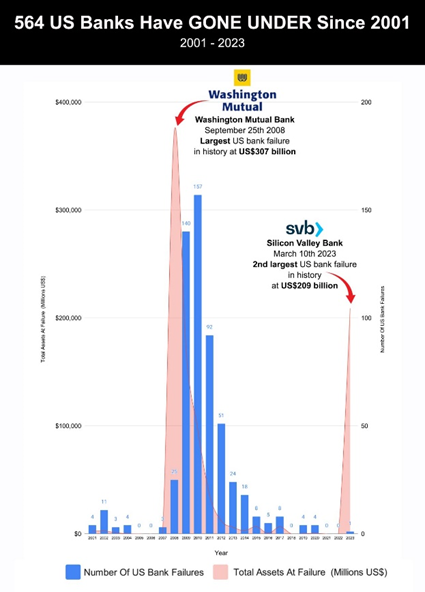

This is pretty scary – the largest US bank failure in history outside of Washington Mutual during the GFC. We said the collapse of crypto-related lenders, banks, hedge funds, and trading houses in 2022 was “isolated” which is sort of true, but even that has had broader effects than we realized initially. And while the cause of the SVB collapse is very different, they are both tied to the theme of an overheated economy. Chasing risky crypto returns and chasing better long-dated returns because of the excess capital sloshing around the startup community.

What will the knock-on effects be? Time will tell but the main liquidity provider for startups has exited stage left and we wonder which other banks and financial institutions have holes in their balance sheet because of the rising rates against their held-to-maturity securities.